Keating's leap of faith

Article by Glenda Korporaal and Paul Kelly in The Australian, December 6, 2013

Keating says: "It was a bit like someone walking up to you with a dirty postcard, the Reserve Bank approaching me" to talk about floating the dollar. Picture: Renee Nowytarger Source: TheAustralian

IT was at a meeting in the late 1970s with James Foots, chief executive of Mount Isa Mines, that "the penny dropped" for the young Paul Keating.

As Keating reveals for the first time in an interview this week, he could see Mount Isa Mines, with its rich seams of silver, copper and zinc, was efficiently run, but its international competitiveness was being held back by the high Australian dollar - at the time running at more than $US1.10.

With little higher education, the boy from Bankstown, in the western suburbs of Sydney, had looked to many mentors as part of a long period of self-education.

He learned from an array of Labor Party leaders and thinkers, from former NSW premier Jack Lang to Rex Connor, the controversial minister for resources in the Whitlam government, who gave him an understanding of the importance of Australia's mineral wealth.

As the opposition spokesman for minerals and energy from 1976 to January 1983 (the portfolio took on several different names), Keating began meeting some of the leaders of the mining industry, here and overseas.

Foots took it upon himself to educate the young Labor politician at a time when many in Australian business had bad memories of the last days of the Whitlam government.

The young Keating realised that, no matter how efficient an Australian industry was, the country's economic future was trapped by the protectionist wall of its high fixed exchange rate.

In a frank interview with The Australian, he describes the meeting with Foots.

"At Mount Isa in Queensland we had one of the most efficient mines in the world, yet with the high exchange rate it couldn't compete," he says.

So when the 39-year-old Keating began his term as treasurer in March 1983, with the incoming government led by charismatic former ACTU leader Bob Hawke, he arrived with a clear view that Australian industry did not stand much of a chance if it was being priced out of the market.

One of the first moves of the new government was to depreciate the exchange rate by 10 per cent.

But Keating could see how having a fixed exchange rate meant Australia had little control over its monetary policy.

Defending the currency meant the government having to buy and sell bonds, with domestic interest rates and anti-inflationary policy subject to the whims of the international markets.

The rigidity of being a small country with a fixed exchange rate in an increasingly global world meant the Australian economy was often forced into a recession in the event of external shocks, particularly those driven by changes in the prices of its exports.

"Before the float it was impossible to run an effective monetary policy," Keating says.

"The average rate of the Australian dollar for the 10 years to 1983 was $US1.17. It was often around $US1.30. This was the authorities - Treasury, Prime Minister and Cabinet, and the Reserve Bank - trying to overvalue the dollar to get downward pressure on local prices.

"We needed a big fall in the exchange rate to restore the nation's competitiveness. Once you had a terms of trade shock, the impact went into domestic interest rates. This is what gave us the recessions in the 50s after the Korean War boom, and again in the 70s."

But having moved the exchange rate down, soon after it came into government, the Labor government had to deal with the fact smart players in world markets were circling and the country was vulnerable to the shifting views of international speculators.

"The markets had got our number," Keating recalls.

Trying to hold the exchange rate meant "they were playing you like a trout on a line", he says.

Keating outlines the behind-the-scenes events that led to the historic decision to float the Australian dollar 30 years ago on December 12, 1983.

Looking back, it was one of the most important decisions in Australia's history, a pivotal step that opened the Australian economy to the rest of the world. It was probably inevitable that it would happen at some stage. But 30 years on, with many politicians on both sides of the fence decidedly lacking in political courage and vision, it is still astounding that an incoming Labor government would have the sheer guts to take the giant leap of faith to freely float the dollar, virtually in one fell swoop.

Having spent years travelling the world talking to leaders in the mining and energy business, Keating had a more global vision of Australia's place in the world than many of his parliamentary colleagues.

During the interview, in his office in Sydney's Potts Point, there is a pause in the conversation when we ask Keating if he was, at any stage, afraid about the momentous decision the government was about to make.

But it's clear it was the fundamental lessons of his days in the shadow energy and minerals portfolio that gave him the confidence to drive the decision. Keating says he knew that if the exercise failed he would have been sacked as treasurer by prime minister Hawke - despite the fact they were, at that time, still close colleagues.

Hawke agreed with the decision, Keating says, knowing that Keating "was prepared to be the lightning rod with my copper spike on the top of the tower to take whatever electricity-laden cloud came along. If it fails then the treasurer goes. Hawke's political risk was over, but in this case the treasurer was prepared to take the responsibility."

It was Keating's relationship with Reserve Bank governor Bob Johnston, who had been appointed by then treasurer John Howard the year before, taking over in August 1982, that was critical to his thinking in 1983, as his first thoughts about the float moved to action.

He describes their meetings and tentative discussions about the float without the presence of the strong-willed secretary of the Treasury, John Stone.

"The Treasury had been vehemently opposed to floating," Keating recalls.

"It was a bit like someone walking up to you with a dirty postcard, the Reserve Bank approaching me to talk about the unapproachable subject."

As Keating reveals this week, he and Johnston had planned to float the dollar across the Christmas period of 1983, allowing the enormous step change to occur during a quieter time for world financial markets. But it was an unexpected inflow of money in the latter half of 1983 that prompted them to move earlier, in mid-December.

As Keating makes clear, the floating of the dollar was part of a broad measure of reforms he implemented, including the opening up of the Australian financial system.

When he took over as treasurer, he recalls, he walked into his office in the old Parliament House in Canberra to see a faded copy of the Campbell report into the financial system on the shelves. Headed by former chief executive of the Hooker Corporation Keith Campbell, it had been commissioned by treasurer Howard, but its recommendations to free up the financial system and look towards a float of the dollar had been quietly put into the too-hard basket.

The new treasurer seized the day, and began removing many long-time controls on the Australian financial system and freeing up the ability of the Australian banks to lend.

In the interview, Keating says he was frustrated that it took three years for the exchange rate to fall, despite comments from the government trying to talk it down. But then it went on a wild ride. The volatility that many had feared from a freely floating dollar occurred.

It was Keating again who was at the coalface in May 1986, with his famous "Banana Republic" comments, which sent the dollar down, hitting a low point of US57c in July 1986.

If Labor had wanted a low dollar, it got it. But the financial markets were nervous.

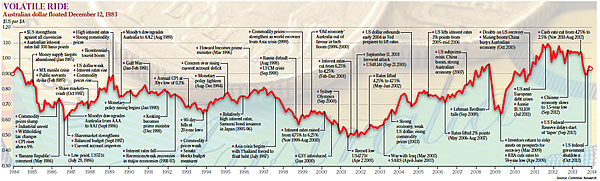

The next 13 years were volatile years for the Australian dollar. It rose to almost US90c in 1988, fell to the mid-US60c range in the early 90s, when the world economy went into a recession, and slumped to a record low US47.73c in April 2001.

The tech boom was at its height and Australia was seen as an old-economy nation.

But, as the accompanying chart shows, the Australian dollar turned in 2001 and began a steady rise upwards again, pushing through parity with the US for the first time since the float.

Keating argues that the floating of the dollar allowed Australia to absorb the shocks of domestic and international changes without going into a recession. The proof, he says, was in the pudding.

"After the East Asian crisis of 1997 the exchange rate fell to US48c and, more recently, with the China terms of trade, it has risen to $US1.10.

"That enormous range meant that - and it's as clear as day - the exchange rate is taking the shock and not the real economy."

The one exception was in the early 90s, when the Australian economy did go into recession. This was driven by a combination of a slump in the world economy and over-lending by the Australian banking sector, thrown open in the late 80s with the addition of 16 new foreign banks, approved by Keating as part of his ongoing mission to open up the economy.

Keating also hints that he was caught by a newly independent Reserve Bank he had created. Having allowed it independence, he had to live with its decision to jack up interest rates.

The upward movement in the Australian dollar since 2001 can be summed up in one word: China.

The recovery of the Asian economies and the growth of China, which joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, increased the demand for the very mineral resources Keating had realised could be a key part of the Australian economy and an important source of export earnings.

It was the sharp rise in Australia's terms of trade - the value of its exports over the value of imports - that drove the currency back up again.

Thirty years on, the Australian dollar is not too far different from what it was at the time of the float - about US90c.

But this time it is perceptions of Australia's links with the Chinese economy, as well as our higher interest-rate regime, that is holding the dollar up higher than many in industry would prefer.

But this time, as Keating says, it is something Australia will have to live with, and the role of policy-makers is to adjust by increasing productivity.

We are part of a global world. There is no turning back.

Click on the above image for enlargement