| Home page | Newsletters |

July/August 2000 Newsletter

The Institute for Private Enterprise promotes the cause of private enterprise and a reduction in the role of government. Subscribers receive copies of all publications including a monthly newsletter complete with attachments.

The following newsletter reports on some aspects of my discussions overseas in June/July with central banks, treasuries, international organisations and think-tanks. I focus on issues not adequately covered or distorted in the media here. Hopefully, the implications for Australia will be apparent.

- CHANCES OF US RECESSION – AND SHAREMARKET COLLAPSE - ARE SLIGHT

- US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION – SOME SUBSTANTIVE DIFFERENCES EMERGE

- GLOBAL WARMING - A DEAD ISSUE IN THE US

- BLAIR – LOSING HIS WAY

- BRITISH MONETARY POLICY ESTABLISHES CREDIBILITY TOO

- UK PRIVATISATIONS CONTINUE UNDER LABOUR

- PRIVATISATIONS WORLD-WIDE INCREASE 10% IN 1999 - MAINLY TELECOMS

- LOW UNEMPLOYMENT RATES IN SOME EUROPEAN COUNTRIES MAY BE A MIRAGE

- AUSTRALIA’S EMPLOYMENT RATE IMPROVES IN 1999 – BUT REMAINS LOW

- GROWTH IS GOOD FOR THE POOR

- “ABORIGINAL” PROTESTS IN LONDON

- ABL PUBLISHES MY ARTICLE ON AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE AIRC

US RECESSION/SHAREMARKET “COLLAPSE” HIGHLY UNLIKELY

What happens in the US economy remains of prime importance (historically, there has been a particularly close connection between what happens here and the US) and most Australian forecasters nominate a US recession and/or sharemarket “collapse” as the biggest risk to our continued growth. However, while that may be correct conceptually, the risk of either event occurring seems slight. True, the US economy has been growing above historical average rates now for some time but improved productivity has caused most analysts (though not Treasury) to lift their assessments of the rate of growth that is sustainable from around 2.5 % pa to above 3.5 % pa. Moreover, while growth has in fact recently been running at around 5 % pa (after five years of more than 4% pa) even as unemployment has fallen to levels where inflation could on past experience be expected to increase, “core” inflation (CPI excluding food and energy) is relatively subdued at just above 2% pa.

Many factors have combined to produce this situation, including:

1.The less regulated labour market and continued illegal immigration from Mexico (estimated at 150,000 pa) have helped contain wage pressures even as the unemployment rate has declined to just above 4%. While debate continues to rage both within and without the Fed about the NAIRU - the level of unemployment that is sustainable without causing inflation – (with well-respected Fed Governor Meyer arguing strongly that it is over 5%), Chairman Greenspan has successfully pursued the pragmatic approach that the NAIRU calculations thrown up by the economic models using historical data are of little value in forecasting inflation in a period of structural change and apparently improving productivity. Greenspan is far from alone in this view. In these circumstances, while the Fed (rightly) assesses that the balance of risks is for inflation to move higher, and while it also takes the view that higher productivity growth requires a higher “neutral” real interest rate than in the past, it is less likely to take pre-emptive monetary policy action because it cannot assume that (apparently) above-trend growth will lead to higher inflation;

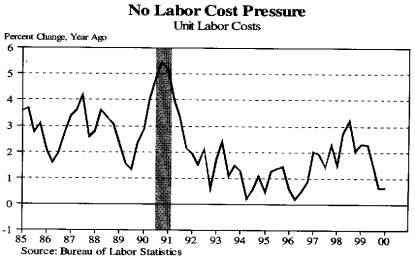

2.This situation is emphasized by the fact, highlighted in the following Merrill Lynch chart, that the much-improved growth in productivity (itself remarkable given the declining quality of labour being employed) has kept the growth in unit labour costs down to extraordinarily low rates. In combination with the competitive labour market, this has prevented the emergence of inflationary pressures on the cost side.

Contrary to the widely publicised analysis by Prof Robert Gordon of North-West

University suggesting that productivity growth has essentially been confined to

the computing industry itself, analysis by the Fed suggests significant

improvements in productivity elsewhere, albeit associated with the use of

computers;

3.Increased competition within US product markets, partly reflecting deregulatory action, has restricted the capacity of businesses to raise prices even in the face of continued strong consumer demand. In any event, any incentive to raise prices has been diminished by the low growth in unit labour costs. This has allowed business to improve profit margins without increasing prices at a faster rate and, at the same time, to achieve strong growth in earnings per share, thereby providing ample justification for higher share prices. In consequence, particularly since the April correction there is little basis for the widespread suggestions that the US market generally is “overvalued”: about 70 per cent of the 500 stocks in the S&P index are priced at only 10-12 times earnings. Of course, there are some sectors that appear very highly priced but a general sharemarket “collapse” is a remote prospect.

4.The improvement in both monetary and fiscal policies has provided an environment less susceptible to fluctuations in economic parameters and thus more conducive to investment and employment. On the monetary side, Greenspan has established great credibility, so much so that it was suggested to me that when he retires the US may have to adopt a formal inflation target (the Fed has none at present but clearly aims to keep inflation below 3 % pa) because no future Chairman could be expected to have the same credibility in keeping inflation under control! On the budgetary side, given that there has been a Democrat President the improvement has been almost as remarkable: since 1992 a deficit of nearly 5 % of GDP has been converted into a surplus of over 1% of GDP and Federal outlays have fallen from 22% to under 19% of GDP - even if one excludes defence and net interest, outlays have fallen by about 1% of GDP. True, Clinton has been restrained by a Republican Congress and helped by the faster growth in the economy. But the fact remains that, however analysed, Democrat Clinton has presided over a reduction in the relative size of government and has presented forward estimates that suggest ongoing large surpluses of over 2% of GDP pa on the basis of the (now) relatively conservative assumption that growth will average less than 3% pa after 2003 - even conservative think-tank Heritage says that Clinton has been “amazingly responsible”.

Of course, surpluses of this size will not survive and both major Presidential candidates have proposals to increase expenditure and cut taxes. But there appears to be a lot to play with and no likelihood that deficits will return.

None of this is to suggest that, at some stage, the US will not slow down and/or that there will not be a (further) sharemarket correction: much depends on how long the remarkable improvement in productivity can be sustained. This is, of course, unpredictable. Importantly, to date none of the signs that usually presage a major down turn, such as excessive borrowing, increasing bad debts or speculative property investment, have emerged. Moreover, the astonishing increase in wealth levels and the sound policy framework provide an enhanced capacity to absorb most “shocks”: it does not seem improbable, for example, that the speculation in technology stocks has been partly funded with “spare” cash that the speculators can afford to lose without reducing other spending greatly. Notwithstanding Greenspan’s credibility, some commentators are saying that the main risk is that the Fed will push interest rates too high.

One has thus to search very hard to find potential problems: for example, could (as recently suggested) the US current account deficit (now around 4% of GDP) really pose a problem when it largely reflects the boom in business investment that is adding to supply? Unlikely. The reality is that the US economy seems almost to be in a virtuous circle in which good policies/institutions encourage increased economic activity and they, in turn, reinforce the good policies.

US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION – AND THE CHANGING NATURE OF WEALTH AND OPPORTUNITY IN THAT COUNTRY

The state of the economy should provide Gore with an advantage and, seemingly, leave few controversial economic issues. However, the US presidential election has developed into a more interesting contest than expected - not because of the candidates (both of whom have rather uninteresting personalities) but because substantive differences have emerged between the candidates on tax, social security reform and schools. This is largely because, behind the “compassionate conservative” image that the spin doctors developed for Bush, he used his lead in the polls to outline policy positions that pushed Gore on to the back foot and indeed forced him to move more to the “right”. Unless he makes a major boo-boo, it is difficult to see Bush losing.

On tax, Bush has proposed a package of cuts over 10 years (which now seems to be the absurd time scale of all politicians’ promises!) totalling $US 1,300 billion and involving across-the-board reductions in income tax brackets to 10-15-25-33% (from 15-28-31-36-39.6%). By contrast, Gore’s tax cut proposals largely involve specific, targeted concessions and involve “only” $US 500 billion because he is proposing to use the surplus mainly to eliminate government debt, which has gone out of public favour.

Perhaps the most interesting development on tax policy (and more generally), however, has been the success of the Republicans in having Congress pass legislation to eliminate estate duty. This initiative “took off” unexpectedly and ended up attracting not insignificant Democrat support in Congress even though the high exemption level means that only about 2 per cent of the estates of those who die each year have been paying the tax ie it is primarily paid by the very rich. While Clinton threatens to veto this legislation, its emergence as an issue appears to reflect a further shift in US public sentiment towards encouraging enterprise and opportunity and away from redistribution. Polling showed that no less than 60% of Americans favoured eliminating the estate tax although only 17% felt they would benefit personally! The National Black Chamber of Commerce (a group that didn’t exist before 1993) campaigned hard for repeal of the tax and 5 of the 36 black Congressmen voted for it.

In another indication of changing public sentiment on the inequality/opportunity issue, recent polling showed that 60% of Americans agree that poor people have the opportunity to get ahead and only 24% favour the government trying to reduce income differences between rich and poor. One economics professor commented that “despite the increase in the dispersion of wealth, there has been great mobility”, with one fifth of the richest 25% in 1999 being nouveau riche compared with 5 years ago.

On schools, although the Federal Government funds only a small proportion of public education (about 7%), the widespread public concern at the poor performance of that system has become a major political issue. Both sides are proposing more Federal funding but the focus of the Democrats, who receive much support from the strong teacher unions, is on retaining the existing system but providing additional funding to poorly performing schools. The Republicans, on the other hand, have recognized the need to introduce a competitive element and are promoting charter schools (effectively self-managing schools within the public system) and even vouchers. Bush’s brother, Jeb Bush, has introduced a quasi-voucher system in Florida (where he is Governor), allowing students to move out of schools that are performing poorly, and George W has hinted that he may adopt such a policy federally. According to New York’s Manhattan Institute, charter schools are now “spreading like wildfire” and, with Florida, three States now have (limited) voucher schemes. (Also interesting is that “bussing” has pretty well stopped and the Supreme Court – which has a 5/4 “conservative” bias – has become less inclined to support regulation designed pro-actively to promote racial equality. The election result will be important in determining whether the Court’s conservative bias will be retained as there are two vacancies coming up).

GLOBAL WARMING – A “DEAD ISSUE” IN THE US

While “greenies” would welcome a victory by Gore (who once said that the internal combustion engine should be phased out!), the reality is that the Congress is not going to pass legislation that imposes restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions in the US except in the extremely unlikely event that there is an international agreement that imposes meaningful restrictions on all major countries. Attitudes of Congress are being increasingly influenced by challenges to the so-called scientific consensus of the 2,500 scientists on the IPCC, such as those of the 19,000 scientists with advanced academic degrees who have signed the petition rejecting the warming claims as unsubstantiated and arguing that, even if the warming claims were to be realized, that would likely benefit the US (and elsewhere). Evidence countering scare-mongering claims by green lobby groups is also receiving more attention – for example, that the area under forest in the US is increasing, not diminishing; and that rain forests are “nothing special” and are not in any event disappearing at anything like the rate claimed. Such developments, along with reports that Greenpeace is experiencing a major loss of membership and funding, and that the entire US board has resigned, all point to rapidly diminishing public concern that “the environment” is seriously at risk.

Against this background, Cato, now probably the leading US think-tank, rightly takes the view that global warming is virtually a “dead issue” politically in the US. More generally, one might venture that “the environment” is now a relatively minor political issue.

BLAIR – LOSING HIS WAY

Athough the UK Labour Government remains well ahead in polling, and the UK economy continues to perform well, there is increasing disillusionment with Prime Minister Blair, who is perceived as (in the words of a document prepared by his own private pollster and leaked to the press) “pandering, lacking conviction, unable to hold a position for more than a few weeks”. The same document advised the PM that the “New Labour brand” is “badly contaminated”. Whether this advice will be fatal for Blair rather than his “spin doctor” depends on whether the Conservatives can exploit the evident failure of the Government to live up to over-hyped claims that it would effect dramatic improvements in public services, most notably in health, education (over 20% are functionally illiterate), law and order and transport. This failure has undoubtedly led to growing skepticism about the trumpeted virtues of Third Way amongst those who have been prepared to give it a go but also amongst its supporters, some of whom have responded by calling for more radical moves to reduce inequality.

In Parliament Hague has been more than matching Blair and he is starting to make some headway in the predominantly left-oriented media. By touting themselves as low-taxers and low-spenders (slower than the projected growth of 2.5% pa in the economy), and even venturing to advocate a form of charter school, the Conservatives have also taken a modest step towards differentiating themselves from Labour. The latter’s response to public disillusionment with the Third Way certainly provides potential for differentiation by offering large tax cuts, which is what the Conservatives are foreshadowing.

Thus, the Government’s solution (sic) to its evident failure to deliver quality services is to throw a lot more money to the public sector. Public spending is projected to increase by 3.25% pa (real) over the next 3 years, which includes (real) increases of 6% pa in education and health and involves a lift in spending from 37.7 to 40.5% of GDP. While it is a measure of Chancellor Brown’s prudence (his favourite word) to date that the latter figure would be lower than in the last Conservative year, this leaves Labour little scope for tax cuts. Thus, the potential battle lines are drawn – tax cuts versus public spending.

BRITISH MONETARY POLICY ESTABLISHES CREDIBILITY TOO

Both the IMF and the OECD have given ticks to the operation of monetary policy and the new monetary arrangements. While there is much complaint from manufacturing industry about the strength of the pound (which puzzles the Bank of England but may largely reflect continued strong capital inflow), the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) that includes outside appointees and decides on rate changes has established credibility by keeping inflation under control while at the same time avoiding any significant slow-downs from the Asian crisis (when rates were cut). The arrangements provide for an inflation target of 2.5% and for the Governor to write an open letter of explanation to the Chancellor if the rate varies by more than 1% either side. The minutes of the MPC are published, including any substantive differences in view within the MPC.

There are some interesting aspects of the comprehensive Inflation Report that the Bank publishes quarterly. First, it provides for two years ahead the MPC’s latest forecast of inflation (excluding mortgage interest rates) showing a range of possible outcomes but with the core forecast probability highlighted. Second, it also includes a table showing the likely effect on the forecast of different assumptions about its components (such as effects of changes in the exchange rate and profit margins). Third, recent inflation forecasts have been allowing for a compression of price-cost margins of 0.25-0.3% pa to reflect technological advances and competitive pressures ie it has been assumed that there is at least a temporary structural downward pressure on inflation, including from regulatory requirements imposed on utilities. Fourth, it is explicitly stated that the inflation forecast assumes that productivity growth will be only at the 40year average of about 2% pa, although it is acknowledged that this could be conservative. Fifth, the Bank surveys and publishes other forecasters’ inflation expectations.

With inflation around 2% pa, the existing cash rate of 6% has been maintained since February in the face of the Fed increase to 6.5% and despite a sharp jump in wages growth (attributed to temporary factors) and a tightening in the labour market, with unemployment falling below 6% and widespread reports of labour shortages. The Bank clearly gives little weight to estimates of the NAIRU but does take specific account of trends in the proportion of the working age population that is not actively searching for work. This proportion has been falling very slowly but is still over 20% and is regarded by the Bank as a “safety valve”. The Bank noted in its February report that, over the past two decades, a number of reforms in employment legislation and the tax/benefit system may have reduced the structural unemployment rate and says that the recent re-regulatory measures (such as the introduction of a minimum wage) appear to have had few adverse effects.

UK PRIVATISATIONS CONTINUE UNDER LABOUR

The Labour Government is continuing to respond to poor performance in the public sector by privatizing and/or contracting out and media reports suggest that it has even decided to give up Government holdings of 12 “golden” shares in companies that were established when utilities, such as in the electricity and gas industries, were privatised. Despite a Quiggin-type proposal to finance investment in the run-down London Underground by government borrowing (on the fallacious argument that it would be “cheaper”), that operation is being partially privatized, with two expected franchisees to get 30 year contracts; the operation of Brixton prison is to be contracted out (a first for an existing prison) after the poor performance of the publicly employed warders there; reports suggest that some of Britain’s parks may also be partially privatized, along with the air traffic control system.

Transport Minister Prescott, who strongly opposed the original privatization of the rail system, nonetheless accepted that the Government should proceed with re-franchising the agreements that are soon to expire. Had the Government thought the public sector could have done better, it could have decided to take over from private operators as the franchise agreements expire. Prescott has also announced the Government will make available over the next ten years substantial public funds for subsidizing uneconomic services (the present subsidy runs at something over one billion pounds a year) and for infrastructure improvements. The new arrangements are based on an assumed large increase in rail usage.

Some Australian commentators have proclaimed the failure of the privatization of the UK rail system. However, the original privatization was undertaken in a context where it was assumed that rail travel had limited growth prospects and where, as one Transport official put it to me, “something radical had to be done” to prevent the existing system from collapse. In the event, the private operators have succeeded in increasing passenger traffic by 25-30% - but the run-down rail infrastructure has not been able to cope. Moreover, as the franchise agreements were made for only short periods because of uncertainty about how the privatized system would work, the franchisees have had little incentive to invest beyond what was required in their agreements. Thus, while quite a few private operators are performing below punctuality targets and services are often crowded, the deficiencies appear largely to flow from the unexpected increase in usage and the outdated infrastructure. Overall, the view of the Transport Department is that there has been an improvement in performance under privatization.

PRIVATISATION CONTINUES TO INCREASE WORLD-WIDE – AND MAINLY TELECOMS

The latest OECD analysis shows that, world wide, privatizations increased by 10% in 1999 to $US 145 bn, with OECD countries accounting for over two-thirds. The analysis identifies the factors driving privatizations as including “the continuation of a general trend towards reducing the role of (the) state in the economy” and that this involved “a growing trend of asset disposals in the infrastructure sector”. The most important infrastructure privatizations occurred in telecommunications, followed by power sector sales. Over the last decade telecommunications privatisations have accounted for 40% of all OECD proceeds and the frequency of transactions in this sector is “due, in part, to the governments’ efforts to enable companies to meet the challenge of market liberalization.” The year 2000 is expected to result in further large sales in this sector as a result of privatizations/part privatizations in Sweden, Germany (where big price reductions have already been obtained), Japan, and Turkey.

These privatizations have resulted in a very considerable expansion in capital markets, with market capitalization in high-income countries increasing from 56% to 95% of GDP between 1990 and 1998. Importantly, the OECD analysis points out that recent economic research suggests that the deepening of financial markets itself contributes to economic growth, particularly in smaller countries. This presumably occurs through reductions in transactions costs and improvements in the efficiency of capital raisings ie for countries with undeveloped capital markets the benefits of privatization are not confined simply to the improved efficiency of use of resources of the former government enterprises.

None of the OECD’s privatization figures include the mass privatizations in Russia, where it is estimated that 75% of the economy is now in the private sector – but, of course, largely in the hands of the so-called oligarchs.

LOW UNEMPLOYMENT IN SOME EUROPEAN COUNTRIES MAY BE A MIRAGE

One or two Australian commentators have drawn attention to the low unemployment rates in some smaller European countries, such as Denmark (5.2% in 1999), Netherlands (3.6%), Norway (3.2%), Portugal (4.6%) and Austria (4.7%), despite those countries having apparently regulated labour markets. The implication drawn is that deregulation is not a prerequisite to improving labour market performance.

My discussions at the OECD suggest, however, that any assessment of the labour market performances of these countries that looked behind these figures would conclude that the low figures are something of a mirage. In particular:

(i) Their governments have perceived political advantage from reducing the political odium attached to high unemployment figures by allowing many who would otherwise be unemployed to move out of the workforce and onto social security benefits, such as disability and (through early retirement schemes) general pensions. This is particularly evident in the Netherlands, where there is a large proportion of the working age population on the relatively generous disability pensions (the “lost generation”) and where early retirement rates are also high. The OECD’s Economic Survey of March 2000, for instance, points out that “out of a total of some 550,000 persons receiving unemployment benefits, only about 220,000 persons (or 3.2 per cent of the labour force) are registered as unemployed and seeking a job. The remainder are persons who, for various reasons, are not seeking a job. For instance, some 100,000 are over 571/2 years of age and are not required to seek a job. As for the “disabled”, despite several years of corrective efforts, their number remains totally out of line with the general health status of the population or any other objective criteria.” Off the record, OECD officials acknowledge that the Dutch achievements are somewhat less than the “miracle” widely touted in the media.

(ii) While allowing people to move onto pensions or remain on unemployment benefits without having to seek a job, many of these countries have also significantly tightened eligibility for unemployment benefits, pushing particularly younger people into jobs or into participation in labour market programs as a condition for receiving benefits. In the latter case, the placement of such participants in “training” schemes of one sort or another reduces the unemployment rate. Denmark, for example, now has about 2% of the work force on such schemes.

(iii) Partly reflecting (i), the proportion of the working age population actually working is lower in some of these low-unemployment countries than it is in less regulated labour markets such as the US and UK. Further, while a country such as Norway has a higher proportion nominally working, the average annual hours worked (about 1,400) there are significantly lower than in the US (nearly 2000) or the UK (over 1700). This partly reflects Norway’s preparedness to use its large income from oil to maintain high levels of employment (but not hours) in industries that are protected (agriculture and fishing). Similarly, the employment rate in the Netherlands gives a false impression of the level of “real” employment (and of its improvement) because over 30 % is part-time and annual hours worked are as low as in Norway.

(iv) In some countries, labour market regulation is less than it might appear. In Denmark, for example, “wage setting is largely decentralized to the enterprise level, and employment protection is light-handed” (OECD Survey of Denmark June 2000 p54). In Portugal, labour market regulations are often not applied in practice. There are also significant “black” markets in labour comprised of social security recipients who are prepared to work for low wages eg in the Netherlands;

Of course, countries with the less regulated markets have also been pursuing some of these policies. But it is clear that the underlying labour market performance in most “low’ unemployment European countries remains poor.

AUSTRALIA’S EMPLOYMENT RATE IMPROVES – BUT IS STILL LOW

The OECD’s Employment Outlook for 2000, published in June, show s that the proportion of Australia’s working age population (15-64) employed in 1999 rose to 68.2%, a full percentage point increase on 1998. At this level, it is fractionally above the peak reached in the 1980s (68.1 in 1989) but has still not exceeded the peak reached in 1973 (68.6) before the disastrous wage break-out of 1974.

Moreover, our employment rate (EPR) remains well below that in those countries with less regulated labour markets and broadly comparable parliamentary and social security systems. Thus, in 1999 the EPRs for the US, the UK and NZ were 73.9, 71.7 and 70.0 respectively despite their having much higher proportions in the more-difficult-to-employ categories. If we had had even similar proportions employed as in the US and UK in 1999 we would have had another 500,000-700,000 employed – we should have higher proportions employed!

GROWTH IS GOOD FOR THE POOR

While in Washington I was able to have a brief chat with David Dollar, Research Manager of the Development Research Group in the World Bank, who has jointly authored a paper with the above title that has engendered enormous controversy (and hostility from NGOs). He has also jointly authored a World Bank report entitled Assessing Aid which caused a representative of OXFAM to call him a “Neanderthal”. (I have a copy of each document).

I have previously reported that former Commonwealth Statistician, Ian Castles, has showed conclusively that there has been no decline in the share of least developed countries in world GDP (see November newsletter). Dollar’s analysis is much more important because it shows that inequality within the 80 countries covered has not increased and that income of “the poor” (defined as those in the bottom quintile of incomes) has been increasing in line with average income per head (or in periods of crisis has decreased in line). Moreover, Dollar ‘s analysis suggests that “the basic policy package of private property rights, fiscal discipline, macro stability, and openness to trade increases the income of the poor to the same extent that it increases the income of the other households in society.” In short, contrary to the impression created by many economic analysts and the media “globalisation” has been good for the poor too.

His report also concludes that “public social expenditure shows little effect on growth or distribution” … which ..”reminds us that in many countries public expenditure on social services often is not well-targeted towards the poor.”

“ABORIGINAL” PROTESTS IN LONDON

In London I attended the reception in Australia House during the Australia week celebration of the centenary of the legislation establishing the Australian federation. Stationed outside Australia House was a small group of protesters holding placards calling for the Prime Minister to apologise for the stolen generation and accusing Australia of “genocide”. I wandered over to listen to their conversation. They were all clearly “Poms”.

ABL PUBLISHES MY ARTICLE ON AN ALTERNATIVE TO THE AIRC

While I was overseas, the Australian Bulletin of Labour published an article by me on An Alternative to the Australian Industrial Relations Commission. This is on my web site www.ipe.net.au and copies are available on request. The Abstract reads as follows:

“There is a strong case on both economic and social policy grounds for repealing existing legislation regulating workplace relations, converting the AIRC into a voluntary advisory/ mediation service with subsidised services for low wage earners and substituting legislation that codifies common law that would normally apply to contractual relationships between employers and employees. Such an alternative institutional arrangement would need to be accompanied by assurances that low paid workers in low income families who experienced wage reductions would have their living standards protected either by the existing means tested social security system or by changes to that system”.