return to Hot Off the Press list

It is not surprising that left journos have used week-end editions to attack Abbott’s 18C and dames and knights. The AFR’s chief political correspondent (who asked recently that I not send him my comments on any issues) has a rather nasty critique below, including the insertion into the centre of his article of a photo of the Queen and Prince Phillip and a reference to “her majesty retaining her presence on the prawn”. The Fairfax Press and the ABC have (naturally) been heavily critical of the two decisions.

Abbott has not responded directly but he and Morrison have in a press interview today announced “good news”, pointing out that, while there have been no arrivals since Operation Sovereign Borders began, over 600 people have now either voluntarily returned or been forcibly returned to their place of origin.

On 18C The Australian has more than one sympathetic piece (including its editorial) but the one below by Brendan O’Neill is an interesting scan of the history of intrusions into freedom of speech and of legislation in other countries restricting/outlawing racism/discrimination. O’Neill is editor of “Spiked” in London and is to give an address in Sydney next week. His conclusion is that legislation probably doesn’t stop hate speech. There is also the problem that it may inhibit justifiable critiques of extremist organisations.

Henry Ergas’s article highlights the importance of Abbott getting control of government expenditure and the political difficulty of doing so. I have sent a letter to Ed emphasising the need to “educate” the public on the rationale for doing so, including the reduced need for government assistance given the near 50% increase in real per capita incomes over the past 20 years

Des

Contents:

- Tony Abbott – nothing like a dame to distract him - Phillip Coorey (Australian Financial Review)

- Operation Sovereign Borders: Prime Minister Tony Abbott marks 100 days without an asylum seeker boat arrival - Editorial (ABC)

- Government must tackle ever-rising expenditure - Henry Ergas (The Australian)

- How a ban on hate speech helped the Nazis - Brendan O’Neill

(The Australian)

Tony Abbott – nothing like a dame to distract him

Article by Phillip Coorey published in the Australian Financial Review, March 29, 2014

Tony Abbott’s decision to restore knights and dames to the honours system seems old fashioned. Source: Reuters

IJoe Hockey still shudders when he recounts the phone call from John Howard on the morning of Sunday, June 4, 2000.

Hockey, then the minister for financial services and regulation, was taking his morning walk along Bondi Beach.

Splashed across the front pages of the Sunday papers was a decision by the Reserve Bank of Australia to mark the centenary of federation by removing the Queen from the $5 note.

“Off with her head,” screamed the banners outside the newsagents.

Hockey summarises the edict from a fuming Howard: “Put her head back on.” Needless to say, her majesty retained her presence on the prawn.

The incident occurred just eight months after Howard led the campaign to kill Australia becoming a Republic.

His monarchist bona fides need no further explanation and that’s why his disagreeing with Abbott this week on the decision to restore knights and dames in the Order of Australia was so salient.

Even conservatives think it anachronistic

As Howard told The Australian Financial Review, he decided, upon becoming prime minister, against doing the same thing – saying even conservatives would have considered it “somewhat anachronistic”.

He outlined his reasons in his autobiography, titled Lazarus Rising, and said his views have not changed.

As one Liberal confided after reading Howard’s comments: “Great, we’ve outflanked Howard to the right on the monarchy.”

Abbott’s decision to restore the honours, and it was his decision, was a self-indulgence. While he has many similarities to Howard insofar as he has adopted his style of leadership and people management, the restoration of the old honours system shows he has yet to master one of Howard’s greatest skills – understanding the mob.

Abbott was born in England, grew up in comfortable circumstances and rounded off his education at Oxford. Howard didn’t quite grow up on struggle street but his family pumped petrol for a living and was by no means establishment.

This bred in him an inherent understanding of what mainstream Australia, as he liked to call it, would and would not cop, and it served him well during his years at the helm of the nation.

Howard’s embrace of the jubilant national mood during the 2000 Sydney Olympics was perhaps his finest moment in this regard.

Some progress in self-identification

Consequently, he knew bringing back knights and dames would largely be the subject of derision from a country that has made at least some progress in terms of self-identification over the past three decades. In his book, he suggested that bringing back the honours could be detrimental to the cause of the monarchy.

“I knew, however, that I had other fish to fry, and as a strong supporter of the constitutional monarchy continuing in Australia, I did not wish to be seen to be reviving an honour which to many, even conservative, Australians was somewhat anachronistic,” he reasoned.

Abbott’s decision is not the end of the world but it is an overreach, just as when the most underwhelming of royals, Prince Harry, visited in October.

“I regret to say that not every Australian is a monarchist, but today everyone feels like a monarchist,” Abbott opined on behalf of the nation.

Moreover, it reinforced the message, as outlined in this column last week, that the government’s priorities are not where the people want them to be right now.

The timing of the Abbott’s announcement was presumably dictated by the timing of Quentin Bryce handing over to Peter Cosgrove as the next Governor-General. Abbott decreed that incoming and outgoing governors-general would automatically receive what is now the nation’s highest honour.

Inadvertent race debate

The decision came in the midst of the race debate the Coalition had inadvertently started by barging ahead with repealing sections of the Racial Discrimination Act to protect Andrew Bolt.

Another niche issue aimed at a fragment of the Coalition’s base. Another priority misfire.

As one senior Labor MP noted, Abbott and Attorney-General George Brandis, as white, middle-class men, would not have the faintest idea of the impact of their actions. It’s all theory of upholding free speech and understanding nuances of the Racial Discrimination Act.

They can bang on about Voltaire all they like but politics is about perception and the message out there is that the government says it is okay to water down protections against racial abuse.

As one worried Coalition minister noted, playing with the act is like playing with asbestos. Much better you leave just it alone. Don’t break it up unless really necessary. Bolt does not constitute really necessary.

Proposal backfires

It is little wonder the proposal is backfiring in seats with ethnic populations.

As The Sydney Morning Herald revealed on Thursday, the original proposal Brandis took to cabinet was so severe he was rolled by his colleagues and forced to release a draft for consultation.

One of Brandis’s colleagues expressed alarm at how culturally right wing he had become in the few short months of government. “The sooner they finish LNP Senate preselections in Queensland the better,” he said. His theory was that with the Liberal and National Parties merged in Queensland, Brandis was pandering to the rural right to ensure his preselection at the top of the Senate ticket.

Both the knighthoods and the proposed changes to the Racial Discrimination Act capped off what has easily been the government’s worst fortnight, which started with Arthur Sinodinos stepping aside as assistant treasurer.

Sinodinos’s decision to go quickly largely limited the damage but the government muffed its chance to regain the ascendancy. In policy and political terms, two very important events occurred over the past fortnight – Labor and the Greens united in the Senate to block the repeal of the carbon tax, then the mining tax.

Repealing these were signature election promises and while the Senate blocks were expected, the Coalition should have hammered them for days, especially with the WA Senate elections next week. Instead it created the distractions of race politics and knights. Abbott and much of his cabinet will be in Perth next week for a campaign blitz. If the Coalition does not do so well on Saturday, it may rue the past fortnight for robbing it of momentum.

Phillip Coorey is The Australian Financial Review’s chief political correspondent.

Operation Sovereign Borders: Prime Minister Tony Abbott marks 100 days without an asylum seeker boat arrival

Editorial published by the Australian Broadcasting Commission, March 29, 2014

Prime Minister Tony Abbott has declared "the way is closed" for people smugglers as the Government marks 100 days since a boat arrived in Australia's territory.

Standing next to a sign comparing the number of boat arrivals under Labor and the Coalition, Mr Abbott congratulated his Immigration Minister Scott Morrison on progress with Operation Sovereign Borders, which has been tasked with stopping asylum seeker arrivals.

The Prime Minister said Mr Morrison has done an "outstanding" job. "This is the result of ... full and methodical implementation of the policies that the Coalition took to the last election," Mr Abbott said.

"It is too early to declare that the job is done, but nevertheless I think we can safely say that the way is closed."

The Opposition said it is too early to "proclaim victory", but has welcomed the reduction in boat arrivals.

The Government said with the monsoon season coming to an end, the number of boats attempting the journey to Australia may increase.

But Mr Morrison said the first two phases of the operation - 100 days of a reduction in arrivals and the same amount without any arrivals - have been successfully completed.

He said Operation Sovereign Borders will now enter a new phase as the Government focuses on the 30,000 people still in immigration detention.

"We now go into the third phase where we move into the post-monsoon period and the risks are just as great," Mr Morrison said.

"We will maintain the intensity of all of our operations in all areas of Operation Sovereign Borders, both with our offshore processing, with what we are doing at sea and through our disruption and partnership operations all the way up through the region back to source.

"We need to work through the settlement arrangements there and the return of those who are found not to be refugees."

Mr Morrison has released figures showing 606 people have now either voluntarily returned or been forcibly returned to their place of origin since Operation Sovereign Borders began.

The Government says for the first time since 2008 the number of people returning home is now exceeding the number arriving.

Opposition immigration spokesman Richard Marles said the arrangements struck by the previous Labor government have been the main factor in the slowdown in boats.

"It's too early to proclaim victory. This is not a footy match - this is not about score boards and banners and slogans. This is about serious public policy addressing a very, very complicated issue," he said.

Morrison refuses to comment on Manus Island investigation

Meanwhile, Mr Morrison has refused to comment on reports Papua New Guinea police are investigating two Australian suspects in the recent killing of an asylum seeker on Manus Island.

Fairfax Media is reporting witnesses to the violent death of detainee Reza Barati in February have identified two employees from security contractor G4S.

Mr Morrison said it is not appropriate to discuss the police inquiry. "That matter is still before the Papua New Guinean police and as I said I'll be in PNG this week to get a further update on where those investigations are at," he said.

"Our own inquiry is also continuing under Mr [Robert] Cornall and when those matters are brought to a conclusion, if there are any requests that are made obviously we'll work through those requests as appropriate."

Government must tackle ever-rising expenditure

Article by Henry Ergas published in The Australian, 29 March, 2014

AS the Abbott government prepares its first budget, it faces some stark realities. This year will see our sixth budget deficit in a row. And although there may be some short-term improvements, the time bombs Labor left will result in deficits for years to come. Without fundamental change, the country’s fiscal position risks becoming unsustainable.

The causes of the problem are obvious. Commonwealth payments are running at just less than 26 per cent of GDP, 1.4 percentage points above their 20- year average and close to the peak Kevin Rudd and Wayne Swan achieved in 2009-10.

Commonwealth receipts, on the other hand, are projected to be about 23.1 per cent of GDP this year, with tax collections running 0.6 percentage points of GDP below their average level.

Combined, spending that is far above trend and revenues that are slightly below trend translate into persistent red ink, with Labor’s last budget statement projecting a cumulative deficit of $123 billion to 2016-17.

But even more worrying than the immediate prospect is the longer-term outlook. Labor took public expenditure to historic highs, as spending per head of population rose in real terms from barely $6000 before the Whitlam government to about $12,000 by 1998-99, and more than $15,000 today.

And that growth seems set to continue, with a slew of programs increasing the outlays-to-GDP ratio over the next decade to a peacetime record while pushing real commonwealth spending in 2023-24 to an extraordinary $20,000 per Australian man, woman and child.

Yes, with rising incomes and ongoing inflation, commonwealth tax revenues will grow too. But “bracket creep” is difficult to sustain politically; and even if it could be sustained, allowing inflation to force ever greater numbers of income earners to face marginal tax rates of 37 per cent or more would impose high economic costs. Rather, bracket creep can and should be offset by tax reductions, meaning that revenues won’t rise to much more than 25 per cent of GDP.

The result is an annual shortfall of 1.5 per cent of GDP, plunging the commonwealth, which had positive net assets of $44bn at the end of the Howard years, into more than $400bn of net debt by the early 2020s.

As the ratio of net debt to GDP marches towards 20 per cent, the government’s interest costs will rise while its scope to increase borrowings so as to sustain spending when serious shocks hit will dwindle. With our economy increasingly exposed to terms-of-trade fluctuations, the effect could be severe instability, with all the economic, social and political pain that entails.

Averting that danger requires a dramatic improvement in budget outcomes, in the order of 2 per cent of national income, allowing net debt to fall from 12 per cent of GDP today to no more than 5- 6 per cent of GDP within a decade. But no miracle cure can achieve that turnaround.

For sure, nostrums such as drastically curtailing superannuation tax concessions for higher-income earners always get a good run, but they merely show a lack of understanding of just how punitive effective tax rates on retirement savings would be were those concessions removed.

Rather, the answer must lie in tackling the programs that are taking public spending ever higher. Those programs are readily identified; and so too are options that could slow their growth. But, for those options to result in durable fiscal consolidation, they must be associated with comprehensive policy reform.

The age pension is a case in point. With outlays of just less than $40bn growing at a trend annual rate of about 6.5-7 per cent, it represents the largest single source of future spending pressures.

That growth rate could be halved by expanding the means test to include at least some part of the value of the family home; changing the base on which the pension is set, from a proportion of average weekly earnings for males to those for both men and women, while revisiting the indexation arrangements; and further raising the pension age in line with increases in life expectancy and in the reasonable duration of working life.

But making those changes achievable and politically sustainable is hardly easy. In 1974, voters aged 65 and older accounted for 13 per cent of the electorate; that share is now more than 20 per cent and by 2050 it will have increased to more than 30 per cent. Unless those voters have adequate savings, the clamour to increase the age pension will prove irresistible; so changes to the pension must be accompanied by reforms which help provide income security to older Australians, for instance by greatly expanding access to privately funded defined-benefit streams.

Tinkering with eligibility rules is therefore far from being sufficient to durably reduce the fiscal risks associated with the public pension. Rather, the government needs to define and implement a retirement-incomes strategy that ensures efficient and socially acceptable alternatives are in place.

Similar issues arise with healthcare costs, the second largest source of spending pressures. Indeed, commonwealth outlays on the entire complex of health, aged and disability care are rising more than twice as rapidly as per capita GDP, increasing overall commonwealth spending on those forms of care from about $2600 per head today to $4100 in real terms in 10 years’ time.

Here too, there is plenty of scope to trim expenditure through a cocktail of firm spending caps on individual programs (such as the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and national disability insurance scheme), wider use of co-payments, pared-back safety net provisions, more stringent means tests and tougher eligibility restrictions on concessions.

But imposing those changes doesn’t mean they would endure. For example, under the Rudd government’s hospital-funding agreements with the states, the commonwealth’s share of the growth in efficiently incurred public hospital costs will rise from 45 per cent in 2014-15 to 50 per cent from 2017-18 on. The Abbott government could seek to freeze that share at 45 per cent but it would then face a campaign on hospital cuts as fierce as that Howard faced in 2007, when nearly half of all voters judged Labor clearly superior on health issues.

Nor is it obviously efficient to shift healthcare risks back on to individuals and families, as greater co-payments, tighter means-testing and pared-back safety net provisions would all tend to do. On the contrary, if consumers are exposed to much greater risk, they will understandably resist and ultimately reverse the moves to bring public healthcare costs under control.

As a result, for those moves to be sustainable, they must be paralleled by reforms which ensure that an efficient privately funded alternative to publicly provided insurance is available. There should, in other words, be a credible transition path to an insurance model that offers both comprehensive cover and choice to all Australians, while subsidising those, and only those, who cannot pay for themselves.

The complex of outlays associated with families also cries out for reform. Together, family tax benefits, childcare payments and outlays on paid parental leave are likely to rise in real terms from about $7000 annually per family with children in 2013-14 to more than $9000 in 10 years. Yet there is no shortage of problems with that spending, including great administrative complexity, questionable cost-effectiveness (especially for the childcare payments) and the potential of family payments to inefficiently reduce labour-force participation.

Those problems, however, cannot justify simply taking an axe to the programs, as vocal critics of “middle-class welfare’’ invariably contend. After all, a family with a combined income of $110,000 and two children does have a significantly lower ability to bear taxes than one with the same income but no children; and any equitable tax/benefit system will take that into account. But it is possible to support families far more efficiently than we do now.

For example, all the programs, including Abbott’s proposed parental leave scheme, could be combined into a more flexible, voucher-like payment. The much greater value that would give families would create the political room to reduce both the amount and the growth rate of payments, pegging that growth more closely to increases in tax collections.

None of that is to underestimate the difficulties involved in linking serious expenditure curbs in each of these areas to reforms that deliver more for less. But tackling those difficulties is especially crucial for the Abbott government.

The government came to office promising to redress the nation’s finances; but an unavoidable emphasis on far stricter means tests and narrower eligibility criteria for public programs will put the pain of achieving that goal on precisely the voters it needs to attract and retain. Political survival depends on the Coalition offering those voters something in return.

That something should be a way of meeting those programs’ goals both at lower cost to taxpayers and with greater benefit to recipients. For example, families might well accept slower growth in education spending if it was accompanied by a shift to a voucher system which gave all Australian children a genuine choice of schools.

But that hardly means we can have expenditure restraint without tears. The fact of the matter is that Labor promised, time and again, what it knew could not be delivered; and then did everything it could to lock those promises in, all the more so as they transferred taxpayers’ money to its supporters in the public sector unions.

The result is that we face a historically unprecedented run of budget deficits, stretching from 2008-09 to 2023-24 and perhaps beyond, shifting an enormous burden on to future generations. All the options for righting that situation involve painful choices.

Yet Australians have considerable confidence in the Coalition, with the 2013 Australian Election Study showing the proportion of voters expecting the government’s decisions to improve the country’s economy standing at an unprecedented high. The challenge for Abbott and Hockey, as they struggle with those painful choices, is to carry that confidence into the land of 1000 cuts.

How a ban on hate speech helped the Nazis

Article by Brendan O’Neill published in The Australian, March 29, 2014

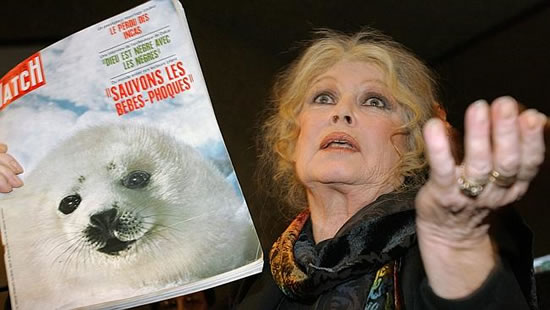

French actor Brigitte has become a vociferous critic of the Islamic ritualised slaughter of animals, describing it as a barbaric practice that is “destroying our country”. Source: AFP

WHAT could an eccentric Swedish pastor, a drunk British student and Brigitte Bardot possibly have in common?

All have been imprisoned or threatened with imprisonment for saying offensive things about minority groups.

The Swedish pastor, Ake Green, was sentenced to a month in jail in 2004 for criticising homosexuality from the pulpit of his Pentecostal church. He described homosexuality as “abnormal, a horrible cancerous tumour in the body of society”.

A local judge decreed that these words constituted a hate crime under Swedish law, which forbids making statements that “threaten or express disrespect for an ethnic group or similar group”.

The British student, Liam Stacey, was sentenced to 56 days in prison at Swansea Magistrates’ Court in 2012 after he tweeted racist comments about black soccer player Fabrice Muamba. Stacey, inebriated at the time of his unhinged tweeting, was found guilty under Britain’s extraordinarily broad Public Order Act, which makes it an offence to “display any writing, sign or other visible representation which is threatening, abusive or insulting”.

As for Bardot, the French movie starlet turned animal rights activist, she hasn’t been jailed for the things she has said, but she has been fined and warned that jail is a possibility in the future.

In her role as animal lover, Bardot has become a vociferous critic of the Islamic ritualised slaughter of animals, describing it as a barbaric practice that is “destroying our country”.

For saying stuff like that, she has been convicted and fined five times under France’s 1881 Law on Freedom of the Press, which makes it a crime to “incite racial discrimination, hatred or violence”, and has had to fork out €30,000.

Those are just three of the thousands of punishments for hate speech doled out in Europe in recent years.

In Canada, too, people have found themselves on the receiving end of censure for saying hateful or disrespectful things about certain groups.

So as Australians hotly debate section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, under which journalist Andrew Bolt was punished in 2011 for criticising “fair-skinned people” who claim to be Aboriginal, it’s worth pulling back and looking at the international context.

Globally speaking, there’s little novel about Bolt’s case. His political criticisms of Aboriginal heritage could just as easily have landed him in legal hot water in Europe and other parts of the world.

The Bolt case is no Aussie one-off — it’s better understood as part of a global war against so-called hate speech, where states are clamping down on what they consider to be offensive words, and in the process are criminalising certain moral, political and religious world views and trampling on freedom of speech.

Section 18C makes it unlawful for individuals to “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” someone because of race or ethnicity.

Attorney-General George Brandis is trying to reform it, suggesting that, in the interests of freedom of speech, the words “offend”, “insult” and “humiliate” should be taken out, but “intimidate” should be left in and joined by the word “vilify”.

Similar laws against hateful or insulting expression exist across Europe and, as in Australia, they’ve been used not only to punish the blindly prejudiced but also those who possess outre views.

So in Denmark it is against the law to “mock or scorn … any lawfully existing religious community”.

Do that, and you can be jailed for four months.

In Finland, anyone who “distributes among the public” words that “threaten, slander or insult on account of race” can be jailed for up to two years.

In Germany it’s against the law to “insult, maliciously malign or defame” people on the basis of race or religion.

France criminalises “any offensive expression, contemptuous term or invective” against racial or religious groups.

In Belgium, anyone who “insults a religious object”, including by “words (or) gestures”, can be jailed for up to six months.

Never shake a fist at a statue of the Virgin Mary if you visit Belgium.

Across the pond, in Canada, the Human Rights Act forbids the public expression of “hateful or contemptuous” thoughts about ethnic minorities and faith groups.

All these laws have been used to punish not just the mad racist who screams the N-word on street corners but also political speech and expressions of religious conviction.

So, in Britain, three Muslims were recently convicted of a hate crime for distributing a leaflet in which the word gay was laid out as an acronym that said “God Abhors You”.

In 2010, a Danish historian was found guilty of “insulting” a religious group after he said in an interview that there was a peculiarly high incidence of crime in Muslim areas.

In 2011, an Austrian writer was found guilty of “agitating against a group” and fined €480 for giving a critical speech on Islam that included the line, “Mohammed had a thing for little girls”.

In 2010, a Finnish politician was found guilty of “incitement against an ethnic group” after he said increased immigration to Finland would increase crime.

We may well disagree with the views expressed in these cases. But they’re nonetheless just views; expressions of strong religious ideas about sexuality or political opposition to immigration. Increasingly in the West, what would once have been seen as legitimate speech in the rowdy fray of public debate is being rebranded “hatred” and punished with fines or jail time.

However much PC packaging is attached to these laws, there’s no dodging the fact they are used to deeply censorious ends, punishing moral outlooks that the mainstream finds offensive.

Where did these laws punishing mockery and offence come from? Tracing the history of hate speech legislation is fascinating, for it tells us a profound and depressing story about the modern West’s bit-by-bit abandonment of free speech.

Modern hate speech legislation was born from World War II. There was a feeling that hatred needed to be curbed to prevent another outburst of fascist hysteria. But it wasn’t Western governments calling for laws against hate speech — it was the authoritarian Soviet Union.

In 1948, world leaders gathered to construct a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Soviet representatives argued that the section on free speech should be qualified by strictures against hate speech. They proposed an amendment making it a crime to advocate “national, racial or religious hostility”. “(We cannot) allow advocacy of hatred or religious contempt,” they said.

Such efforts to water down freedom of speech in the name of combating hate were opposed by Western delegates. From the US, Eleanor Roosevelt said a hate speech qualification would be “extremely dangerous” since “any criticism of public or religious authorities might all too easily be described as incitement to hatred” (how prescient she was). In later discussions, British representative Lady Gaitskell said a hate speech amendment would “infringe the fundamental right of freedom of speech”.

The Soviets lost on the hate speech front in 1948. But they kept pushing. They were finally successful in 1965 with the creation of the UN’s International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Despite the continued opposition of Western delegates and their allies — one of whom said that “to penalise ideas, whatever their nature, is to pave the way for tyranny” — the new 1965 convention did contain a section calling for the criminalisation of “ideas based on racial superiority or hatred”.

It was the spread of this convention into domestic law, everywhere from Austria to Australia, that led to the creation of crimes of hate speech around the world in the late 1960s and early 70s.

So the story of hate speech laws is a story of the West’s slow but sure ditching of freedom of speech. Where once Western leaders opposed the criminalisation of words — “whatever their nature” — more recently they’ve come to see certain speech as dangerous after all, and something that must be punished.

We’re witnessing the victory of the Soviet view of speech as bad and censorship as good, with various members of the modern West’s chattering classes unwittingly aping yesteryear’s communist tyrants as they call for the banning of “advocacy of hatred”, and a corresponding demise of the older enlightened belief that ideas and words should never be curtailed.

Some will say, “So what if we’re finishing off the Soviet Union’s dirty work? At least we’re preventing hatred.” But here’s the thing: history shows that, actually, hate speech laws don’t even help to combat hate.

The Weimar Republic of the 30s had laws against “insulting religious communities”. They were used to prosecute hundreds of Nazi agitators, including Joseph Goebbels. Did it stop them? No. It helped them.

The Nazis turned their prosecutions for hate speech to their advantage, presenting themselves as political victims and whipping up public support among aggrieved sections of German society, their future social base. Far from halting Nazism, hate speech legislation assisted it.

It is surely time every hate speech law was repealed. They are a menace to free thought and speech, and the worst tool imaginable for fighting real hatred.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of Spiked in London. He is speaking on The New Enemies of Freedom at the Occidental Hotel in Sydney next Thursday.

www.cis.org.au/events